Note: This is an elaboration on a post I made on Reddit that I felt warranted its own entry on the blog.

There are a few different approaches I’ve taken to running prewritten material, and the one that I’ve currently settled on is to rewrite the key in a condensed format that prioritizes giving me easy access to information I need to immediately present to my players.

In the past I’ve tried to highlight the existing text in order to save time however in practice I end up highlighting the majority of the text so it ends up costing more time than it saves. I know it works for others, but I was never the sort to be particularly disciplined with my highlighters, so I needed a different solution.

Since I’m know I’m going to end up aggressively highlighting everything anyway, I figured I’d be better off rewriting the key entirely. To avoid giving myself too much extra work , I tried to identify some guidelines for what was “good enough”. To be fair, nothing I’ll outline below is particularly groundbreaking. It’s basically just a mish-mash of Courtney’s keying style in Hack & Slash: On Set Design and the Old-School Essentials house style for adventure writing.

My only innovation, if you want to go that far, is including a short description that tries to touch on a few of the senses of the PCs, in order to have the rooms come alive. I’ve found that focusing on what the characters can immediately perceive helps to both A) avoid rambling boxed text and, B) quickly identify key room elements the players can interact with.

The process doesn’t take me long – it’s best to read the entire key anyway, so I’ll usually have some ideas in mind by the time I start abridging the key. It also doesn’t circumvent the need to sit down and read the entire dungeon or adventure since only skimming the individual keys can lead to you missing out on important background or connective tissue. It does, however, give me a goal-oriented way of interacting with the text. It can be difficult to force yourself to sit down and really read an entire adventure, especially when its a long one, and going at it with a real or imagined highlighter at least gives you a task you can engage with while you read.

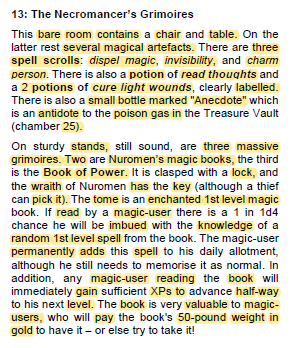

The Key

Key # – Room Name

Short description (one to two sentences), highlighting the 5 senses.

Visible room element 1 (e.g. decor, treasure, monster, door, etc.)

| Additional detail provided upon party interaction.

|| Nested additional detail (when necessary.)

Element 2

Element 3

…

Creature stat lines (with the monster’s name bolded.)

Further Notes

Room Names and Descriptions

I don’t typically read the room names to my players. I’ll try to include decor that indicates what the room is used for in either the initial description or the interactable elements of the room, and players will either figure it out from there or just call the room whatever they like. If the nature of the room does matter due to something like a puzzle, I’ll make sure to double down on that when including interactable elements in the room.

I also won’t go into huge detail on my initial description of any individual room element – I find just highlighting that it exists and letting the players determine what matters to them works best. They miss some secrets here and there but that makes it all the more exciting when they do find them!

Formatting

I go back and forth on whether to use indents, vertical bars or hyphens for separating further detail. It doesn’t end up mattering much since I tend to be consistent within a single document, and I figure either way is fine. I prefer having the stat lines for creature near the bottom because otherwise they can take up a lot of space and get in the way of the flow of the text. In practice the stat lines are superfluous during play since I run games using a VTT, so I may just start omitting them entirely.

Doors and Corridors

In the past I’ve experimented with having a section underneath the room name reminding me of the connections to other rooms, but I’ve found recently that including doors or corridors in the element list helps better. It gives me space to describe both sides of a door in the room key where the players will actually find them, and reminds me where the party will go right next to how they’ll get there.

I have been thinking of including doors in the dungeon key as their own separate keyed entry. I’ve seen it done a few times in modules and I can understand the appeal – it gives you more room to describe trapped doors and note minor specifics like which way the door opens. That might sound like a small deal, but when your party is fleeing from a pursuing monster they’ll certainly want to know! I’m still 50/50 on it for now, and it does add more time and effort to the process but time will tell if it’s worth the trouble.

Avoiding Redundant Information

A helpful piece of advice I’ve received is that you don’t need your key to fill in for common sense – if a room is a kitchen, you can rest assured that you or anyone else reading the key will be comfortable enough with the idea of a kitchen to improvise the background details . It’s a common refrain by reviewers I follow and one I’ve tried to internalize in my own writing. Avoiding over-keying, especially with mundane information, can help make your more comfortable with low-stakes improvisation during the game as well as saving you time and space to prep the things that really matter.

On Avoiding Burnout

One thing I do want to leave you with is any formula you follow as the GM (or DM, Storyteller, etc.), whether it’s this one or your own, should be measured in terms of its value at the table to prep time ratio. It’s easy for your GMing process to calcify and to feel forced to do things because you’re under the belief that that’s the way they should be done.

At the end of the day though, I try to make sure to remind myself that this hobby is ultimately about playing a game with my friends, and that I shouldn’t find myself working so hard I burn out and just quit entirely. Most players (I hope) appreciate the work their GMs put into making their game happen week after week, and you shouldn’t lose sight of that. This isn’t a justification for being unprepared, but forcing yourself to do unnecessary prep can just as easily harm your game as help it.

Leave a comment